Over the past year, there have been repeated security breaches at the White House involving intruders jumping over the perimeter fence. Three years ago, a man opened fire from a car on Constitution Avenue, breaking the outer pane of a window in the private quarters of the president and his family. Clearly, corrective measures are needed to guarantee the safety of the First Family—and temporary barriers are once again in place along the Executive Mansion’s Pennsylvania Avenue frontage, joining the barrage of unsightly barriers on the south side of the White House.

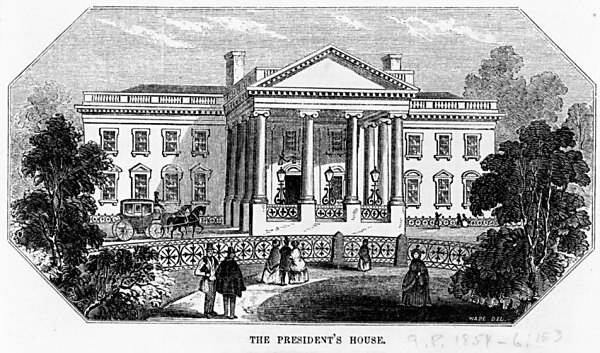

Once an open estate, the President’s House was enclosed around 1820 with a simple iron fence, then later with a Victorian-era decorative iron fence lining the curved driveway, as shown in this 1853 engraving. (Image credit: Library of Congress)

Over time, the White House property has evolved from a villa within open grounds to an increasingly fortified complex. Originally on a single lot between East and West Executive Avenues, the White House now is at the center of a larger controlled security zone that stretches from 15th to 17th Street and from H Street to Constitution Avenue, requiring the closing of Jackson and Madison Places, East and West Executive Avenues, Pennsylvania Avenue, and E Street within the last 30 years. While the needs of security are understandable, the impact on the surrounding city has been drastic—particularly for Pennsylvania Avenue, now only a vestige of its former role as the city’s main street.

The White House complex with the residence at the center—now a multi-block secure area stretching from Lafayette Park (foreground) to the National Mall, and which includes the Treasury Department (left) and Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB, right)—has required the closing of many formerly public streets. (Image credit: Carol Highsmith / Library of Congress)

The recent incidents of intrusion into the White House complex have involved both a fence—which, at seven feet six inches, is possible to scale—and compromised operations in detection and apprehending intruders. Certainly, it is very difficult to prevent a determined trespasser from jumping a fence, but the kind of “no-climb” fences that can actually prevent it are hard to imagine ringing the White House grounds. There are ways to make a higher fence appropriate for its context, although it’s a fine line between appropriate and overwhelming.

A highly ornate fence—approximately 12 feet tall and related to the Georgian style and imperial scale of Buckingham Palace in London—protects an official residence of a head of state. (Image credit: Associated Press / EPA)

Since the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, and even more since 9/11, heightened security requirements in Washington have altered the relationship between the public and many of our government buildings—museums, monuments, and government offices—with bollards, security screening posts, and closed streets. Most of the federal projects reviewed by the Commission of Fine Arts today include perimeter security barriers, from double fences around secure office campuses to stone retaining walls integrated into the landscape of national memorials.

Security requirements vary for federal facilities, but the most successful ones do their job of protection while contributing to the public setting. This example at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History uses the simple modern language of the architecture to create a harmonious vehicular barrier along Constitution Avenue. (Image credit: Beyer Blinder Belle)

When Pennsylvania Avenue north of the White House was closed in 1995, the city’s street network suffered, but the space itself was redesigned to make pedestrians feel welcome. There is a balance to be found between openness and security, and during design review, the Commission and its staff work with agencies to make security installations as open and transparent as possible while minimizing the effect of the installations on the public environment.

Addressing the recent security problems will require some modification to the perimeter security elements along Pennsylvania Avenue, which was reopened as a public space for pedestrians in 2004. (Image credit: Elizabeth Felicella / Michael Van Valkenburgh)

The security of the White House and the protection of the president cannot be solved by a higher fence alone. We encourage the Secret Service and the National Park Service to think holistically in addressing the issues of threat on many levels: physical, operational, and as a wider protected zone. Any solution must be an effective combination of physical barriers and operational procedures to prevent further intrusions. However, the real opportunity lies in a comprehensive approach to the White House security zone: to clean up the accumulation of “temporary” barriers, booths, and screening facilities located on lawns, sidewalks, and roadways—including the Treasury Department, the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, and the National Park Service properties of the Ellipse (President’s Park South) and Lafayette Square.

The current landscape along E Street looking northward to the White House is a hodge-podge of temporary and permanent security elements. Nearby structures for visitor screening, guards, and even mechanical equipment create an undignified environment for the national seat of executive power. (Image credit: Pete Thompson/WAMU88.5)

Meanwhile, plans to redesign the E Street frontage—currently a repellent array of jersey barriers, bollards, and fences—are on hold, as is the General Services Administration’s 2011 proposal to consolidate many temporary entrance screening facilities around the EEOB into an elegant pavilion under the building’s north plaza facing Pennsylvania Avenue. We agree with the recent Washington Post editorial, “No change should or need impinge any further on the White House’s historic openness. Security concerns need not block the American public from its heritage.” The best solution is the one that intrudes the least, and offers in return for its fortifying function the reminder that the public is welcome—and safe—at the national seats of power.

The winning design from the 2011 President’s Park South design competition sponsored by the National Capital Planning Commission would rehabilitate the E Street corridor with an inviting but secure public space. (Image credit: Rogers Marvel Architects)

7 Comment(s)

Phil Zimmermann 29 March 2015

George Watson 29 March 2015

CKYM 30 March 2015

Dantes 30 March 2015

Sheila K 30 March 2015

John J. Landers 20 May 2016

harry 9 June 2016